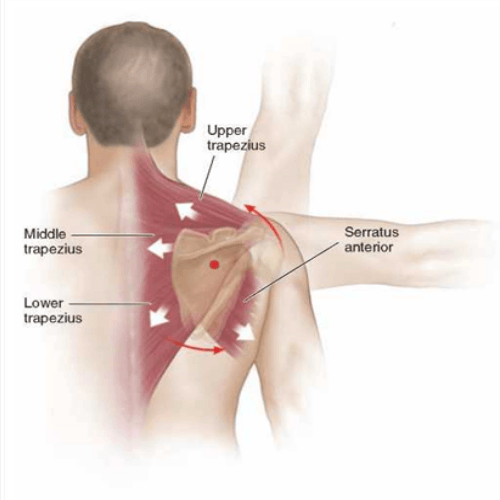

Importance of the Scapula in Shoulder Pathology

Each week we help numerous patients with various shoulder conditions, including bursitis, rotator cuff tears, and post-surgical rehabilitation. A key factor in successfully returning these patients to their pre-injury activities, work and function is evaluating and addressing scapula dysfunction that may be present.

The scapula provides an attachment for several key muscles for optimal shoulder function, including the trapezius (upper, middle, and lower portions), rhomboids (major and minor), serratus anterior, levator scapulae, and rotator cuff. These muscles work in a coordinated manner to facilitate efficient scapula and arm movement. When the scapula fails to function in its intended manner the shoulder is more susceptible to injury. A common presentation is the weakness of the serratus anterior and/or lower trapezius muscles, with concurrent tightness of the pectoralis minor.

Now some people may have poor scapula mechanics without even knowing and function without any noticeable deficits. However, there is likely to be progressive damage occurring that can prove costly. Think of a car with the wheel alignment slightly out. The car will still function but there will be increased wearing of the tyre and possibly other structures. What will the difference in cost be if the wheel alignment was corrected early on versus 12 months later? This is an example where early intervention can help mitigate the risk of future complications.

Exercise Rehabilitation:

The focus of the rehabilitation programme will be based on the findings of the functional assessments. The programme will generally commence with a focus on restoring range of motion and addressing areas of tightness. Interventions are included to improve the resting alignment of the scapula, and progress to address dynamic control (i.e., with movement). As progress continues to be made, the exercises will adopt postures specific to the individual’s hobbies, activities of daily living, and work. Below are examples of two exercises to improve scapula control with varying levels of difficulty:

Fitball wall roll

Action – press the ball into the wall and slowly extend arms towards the ceiling.

Considerations – ensure scapula control is maintained on the lowering phase.

Crawl:

Action – simultaneously move one arm and the opposing leg forward. Continue to move forward in a crawling manner.

Considerations – hand, wrist, or elbow issues. Prescribed towards the latter stages of rehabilitation.

Completing a structured exercise rehabilitaiton programme over a period of 6 to 12 weeks is extremely beneficially and is expected to faciliate improvements in function and a progressive return to pre-injury activities and hobbies. However, continuing with a maintenance programme is vital to preserving the muscular recruitment patterns. Just like brushing your teeth, including exercise as part of your daily routine is a step in the right direction.

If you would like more information on how exercise rehabilitation can assist you, please don’t hesitate to contact us at info@absolutebalance.com.au

Daniel D’Avoine BSc(ExerSc&Rehab)

Exercise Rehabilitation Team Leader – Workers Compensation Specialist

References:

Castelein, B., Cools, A., Parlevliet, T., & Cagnie, B. (2016). Modifying the shoulder joint position during shrugging and retraction exercises alters the activation of the medial scapular muscles. Manual Therapy, 21 , 250-255.

Paine, R., & Voight, M.L. (2013). The role of the scapula. International journal of sports physical therapy, 8 (5), 617-629.

Shiravi, S., Letafatkar, A., Bertozzi, L., Pillastrini, P., & Tazji, M.K. (2019). Efficacy of abdominal control feedback and scapula stabilisation exercises in participants with forward head, round shoulder postures and neck movement impairment. Sports Health, 11 (3), 272-279.

Yildiz, T.I., Turgut, E., & Duzgun, I. (2018). Neck and scapula-focused exercise training on patients with non-specific neck pain: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Sports Rehabilitation, 27 , 403-412.