Scapula Dyskinesis: its impact on shoulder stability, pain, and rehabilitation outcomes

The scapula plays an essential role in optimising the shoulder’s function, offering a position of support and motion of stability (Kibler & Sciascia, 2010). The scapula position enables muscle activation and strength development to enable force and energy transfer of the kinetic chain. The role of scapula plays a pivotal in injury management and rehabilitation for multiple shoulder pathologies (Kibler & Sciascia, 2019).

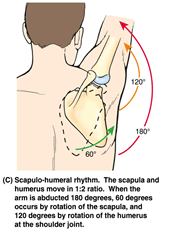

Scapula dyskinesis is a term that describes the dysfunctional movement of the scapula (Paine & Voight, 2013). Normal scapulohumeral rhythm is the synchronised movement of the scapula and humerus to shoulder motion, which is an essential factor for efficient shoulder function. Scapula dyskinesis interrupts normal scapulohumeral rhythm, which can lead to the scapula’s position and stability being put in a vulnerable situation. There is evidence to suggest that poor scapula rhythm can lead to shoulder pain and instability or be an underlying issue of overuse injuries (Pain & Voight, 2013; Moseley et al., 1992; Kuhn et al., 1995). Thus, implementing exercises addressing the scapula’s mechanics plays an important role.

Rehabilitation for scapula dyskinesis

Rehabilitation of scapular dyskinesis requires addressing the causative factors that create the individual’s abnormalities, then focussing on the restoration of the balance of muscle forces that allow for optimal position and motion (Kibler et al., 2013). Implementing exercises to address the causative factors and the mechanics of the scapula is an effective strategy to offer a position of support and motion of stability for rehabilitation.

- Causative factors can include:

- Neurological factors: thoracic, spinal/dorsal scapula nerve palsies.

- Joint derangement: labral injury, glenohumeral instability, bicep tendinitis, rotator cuff tears.

- Bone factors: clavicle and scapula fractures.

- Mobility and flexibility issues.

When looking at the current literature, multiple clinical studies have reported that the incorporation of scapula exercises in rehabilitation programmes has led to positive patient-rated outcomes in patients with impingement syndromes and self-reported instability (Kromer et al., 2013). Another study concluded that patients who had suffered full-thickness rotator cuff tears showed that a rehabilitation programme comprised of scapula exercises reduced overall symptoms and resulted in up to 80% of patients opting for no surgery (Kuhn et al., 2013). These studies demonstrate that implementing exercises addressing the underlying issues of scapula dyskinesis can improve patient-rated outcomes and overall symptoms. Therefore, addressing the causative factors of scapula dyskinesis and prescribing exercises targeting the scapula’s kinematics is an important contributor to providing a holistic approach to shoulder rehabilitation.

If you would like more information on shoulder injuries or other rehabilitation programmes that Absolute Balance can provide, please do not hesitate to contact us at info@absolutebalance.com.au.

David McClung

(B.Sc. Exercise Science and Rehabilitation (AEP, AES) (ESSAM))

Regional Manager – NSW/ACT – Accredited Exercise Physiologist

References:

Kibler, W. B., & Sciascia, A. (2010). Current concepts: scapular dyskinesis. British Journal of Sports Medicine , 44(5), 300-305.

Kibler, W. B., & Sciascia, A. (2019). Evaluation and management of scapular dyskinesis in overhead athletes. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 12(4), 515-526.

Kibler, W. B., Ludewig, P. M., McClure, P. W., Michener, L. A., Bak, K., & Sciascia, A. D. (2013). Clinical implications of scapular dyskinesis in shoulder injury: the 2013 consensus statement from the ‘Scapular Summit’. British

Journal of Sports Medicine

, 47(14), 877-885.

Kromer TO, Tautenhahn UG, de Bie RA, et al. Effects of physiotherapy in patients with shoulder impingement syndrome: a systematic review of the literature. J Rehabil Med 2009; 41:870–80.

Kuhn, J. E., Dunn, W. R., Sanders, R., An, Q., Baumgarten, K. M., Bishop, J. Y., … & Ma, C. B. (2013). Effectiveness of physical therapy in treating atraumatic full-thickness rotator cuff tears: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery , 22 (10), 1371-1379.

Kuhn, J. E., Plancher, K. D., & Hawkins, R. J. (1995). Scapular winging. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 3(6), 319-325.

Paine, R., & Voight, M. L. (2013). The role of the scapula . International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 8 (5), 617.

Moseley JR, J. B., Jobe, F. W., Pink, M., Perry, J., & Tibone, J. (1992). EMG analysis of the scapular muscles during a shoulder rehabilitation program. The American Journal of Sports Medicine , 20(2), 128-134.